Firecall looks back on a Dublin Fire Brigade mass casualty training exercise held last July, with trainee paramedics responding to a simulated large-scale terrorist attack in Broadstone.

Trainee Dublin Fire Brigade paramedics were given a baptism of fire last July, tasked with responding to an unknown mass casualty incident on the Luas line between Broadstone and Cabra, revealed as a terrorist attack with a large number of injured and deceased civilians.

Dublin Fire Brigade has had a working relationship with Luas over the past number of years concerning the Cross City works, ensuring they can respond to emergencies in and around roadworks adjacent to the new Luas line. The track is due to open to the public by the end of the year, but DFB officials wanted to run an exercise with Luas before trams hit the tracks. And, given events of the last year or two in London, Manchester, Paris and Nice, it became clear that the opportunity to train for a potential terrorist attack on Irish soil could prove highly useful.

Third Officer John Keogh made the initial contact with Luas and other stakeholders – a long process involving indemnities, insurance and other administrative tasks, with final approval coming just four weeks before the deadline. The Luas line between Broadstone and Cabra was chosen because it’s one of the few sections isolated from the main roads, winding along the old rail network.

“Using Broadstone as the base, we saw the opportunity of checking out some of the scenarios that might be in place if an incident happened on the Luas track where we hadn’t got direct access off the road. It was an opportunity we didn’t really want to miss out on,” T/O Keogh explains.

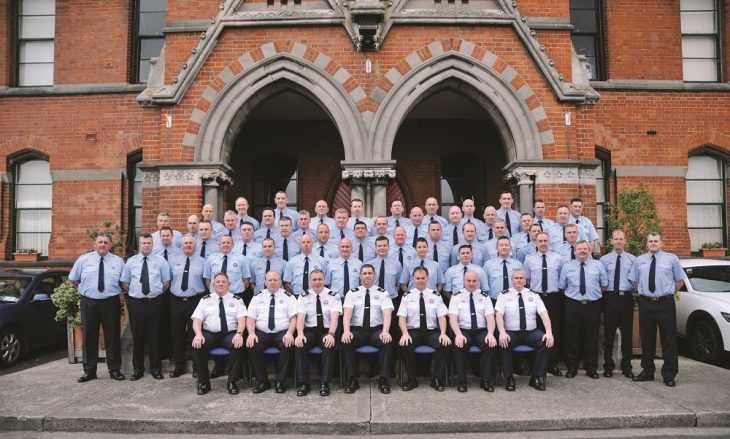

The scene of the training exercise. Photos courtesy Trevor Hunt and John Keogh

ORGANISATION

With permission granted for the exercise to go ahead in Phibsboro, the task of organising the incident itself fell to paramedic tutors A/SOFF Karl Kendellen and A/S/O Derek Rooney, charged with fleshing out the details and looking after everything from logistics to compliance with health and safety, traffic management and more. They crafted a highly realistic scenario for what would be the largest mass casualty exercise in DFB history, with 44 trainee paramedics, 60 casualties, and members of the gardaí, ERU, ASU, the Civil Defence, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland and Luas among those involved on the day.

Testing both the skills of the paramedics and communication lines between DFB and Luas, the exercise began with a call confirming a potential terrorist incident on the line, with an ambulance manned by two recruits arriving from Phibsboro fire station – the station that would turn out to a real incident along this route. The scenario saw four terrorists crashing a car into a tram, overturning the vehicle on the tracks before entering the tram and shooting and stabbing passengers. A second incident later in the day saw an attack on another tram by a second terrorist cell.

“One of the things we did differently from previous years, and to try and make it more realistic, was that we staggered the response and the numbers that were allowed into the incident at any particular time,” says A/SOFF Karl Kendellen. “If an incident happened for real in Dublin, we wouldn’t have 30 or 40 paramedics turning up at the same time – you might only have one or two fire appliances or ambulances, depending on the information that’s given.”

Members of the Garda Emergency Response Unit (ERU), backed by the Armed Support Unit (ASU), cleared the scene before the paramedics could begin triage as per the PHECC clinical practice guidelines. Patients were removed by order of severity to a treatment tent before transportation to a field hospital set up in No. 3 and manned by Dr Niamh Collins, a consultant in emergency medicine who is heavily involved in the DFB training programme – a training exercise for her team also.

“It’s really important for us to build up links with these people. These are agencies that we are working with all of the time – a smiling face of somebody you know helps, particularly in a highly tense environment like this,” says co-organiser A/S/O Derek Rooney, whose primary brief was to produce a risk assessment for the exercise, identifying potential hazards and ensuring the risks were controlled. “[The recruits] were brilliant, in fairness to them. They had a carry, from the initial incident near Broadstone, of approximately 400m. They were in full PPE, which obviously is hard work anyway, carrying 15 or 16 stone – colleagues and members of the public who volunteered and were moulaged (mock injuries), so they had real-life injuries, and a lot of them were shouting and roaring which put a lot of pressure on the recruits. It went very well. A thorough success from everyone concerned.”

Trainees in action.

LESSONS LEARNED

The exercise was a huge success, a large-scale operation that went off without a hitch, and the paramedic trainees excelled on the day. The exercise also highlighted where DFB’s response to such an incident could be improved and further strengthened the links between the emergency response agencies and medical crews who would work side-by-side in the event of a real attack.

“It was great to be a part of, it was a real achievement by everybody. The work that the paramedic tutors and the paramedic trainees themselves put in into making it a success just can’t be quantified,” says T/O Keogh, who notes the efforts made by Broadstone, Luas, Transport Infrastructure Ireland, Dublin Civil Defence, Sisk, the Order of Malta and St. John’s Ambulance in ensuring everything went as planned, and for facilitating their every need on the day. “I just can’t describe how much of a success it really was. To have everybody fully compliant, doing what they were tasked to do without any problem whatsoever – it was a pleasure to be involved in.”

In addition, he touched on the need for resilience and their ability to bounce back – some of the calls received by emergency service controllers can take their toll, and care and support from their loved ones at home is very important to cope with trauma.

In addition, he touched on the need for resilience and their ability to bounce back – some of the calls received by emergency service controllers can take their toll, and care and support from their loved ones at home is very important to cope with trauma.