With the number of electric vehicles set to increase on Irish roads in the coming years, Dublin Fire Brigade is training recruits to deal with potential incidents, writes Conor Forrest.

Depending on who you ask, the motoring world is on the cusp of an electric vehicle (EV) revolution. With diesel’s reputation on the ropes, many of the world’s car manufacturers now feature a hybrid or fully-electric vehicle in their line-up. Volvo announced recently that all cars it produces will use electric or hybrid power from 2019. Plans have been made in the UK to ban the sale of diesel and petrol cars and vans from 2040, with similar moves underway in France, Norway and the Netherlands. Ranges are increasing, charging times are dropping, and drivers across the world are being offered incentives to make the move. Everything considered, it seems that things are swinging in favour of EVs.

The technology has actually been around for quite a while. The first electric vehicles appeared in the 19th century and we’ve been using them ever since – milk floats, forklifts, golf carts and bread delivery vans to name a few. So perhaps it’s fair to say we’re coming full circle rather than witnessing the advent of a completely new technology. In Ireland we’re a little behind the curve – carrots to encourage EV ownership are minimal compared to some of our European counterparts, and just 3,000 or so have been sold here over the past few years.

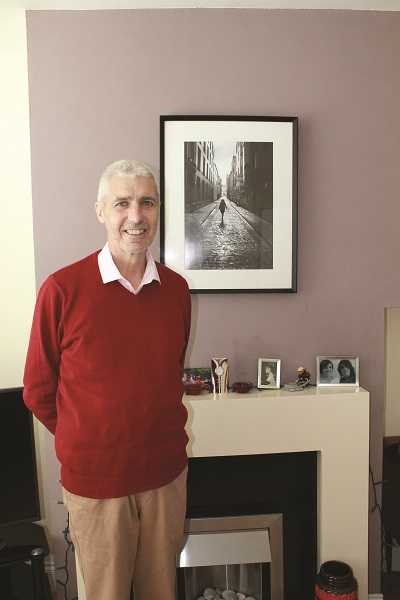

“That’s going to change dramatically. The analogy I would use is when we were all driving petrol vehicles and the road tax situation changed, with road tax based on CO2 emissions, so everyone swung across to diesel,” explains FF/P Richard Hunter. “In the next two to three years you’re going to see a big swing from diesel to electric.”

EDUCATION

Richard’s background is in the motoring industry, having worked for Renault Ireland before joining Dublin Fire Brigade 15 years ago. With a deep-seated interest in EVs, he contacted his old employers when these vehicles first landed on Irish shores at the beginning of the decade, requesting information regarding their safety.

“As a brigade, we have to be proactive rather than reactive. We have to understand the technology, how it’s coming, how it’s changing,” he explains. Such understanding must be fluid, necessary due to the rapid pace of change within the industry. The last few years alone have seen huge strides made in lithium-ion battery technology, with manufacturers decreasing charging times and increasing range – key factors for consumers hesitant in getting rid of their fossil fuel transportation. Better range, lower prices and a wider variety of Government incentives such as free tolls and parking will see the number of EVs sold here spike in the coming years, and Ireland’s emergency services have to be prepared.

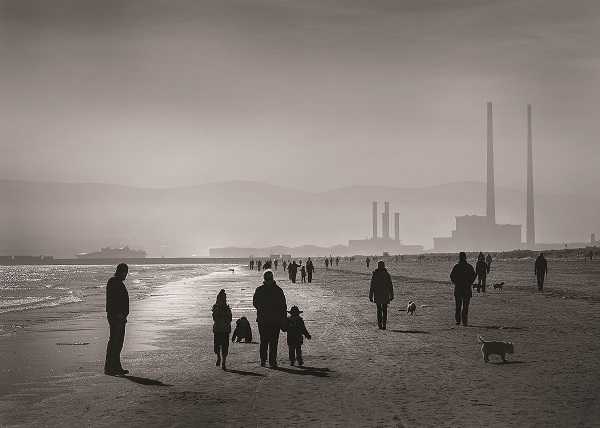

Above: Recent training in Clonmel, Co Tipperary for the National Fire Directorate. Photo: Richard Hunter. Main image: Renault’s range of zero emissions vehicles. Photo: Renault Marketing 3D-Commerce

The end result of Richard’s fact-finding mission was an emergency response guide to safely dealing with EVs involved in road traffic collisions (RTCs), which has been taught at training programmes in Tipperary for the National Fire Directorate and has been part of the curriculum for new DFB recruits over the past five years. DFB’s EV course is focused on making firefighters aware of the ins and outs of the average EV, tackling urban myths and educating firefighters about how these vehicles work, such as their silent nature (no rumbling engine) or how to recognise an EV (blue-tinted lights, ZE – Zero Emission – badging throughout, and the absence of a tailpipe). “Straight away, even if you haven’t done the training course, something is going to be telling you there’s something a little bit different about this car,” says Richard.

There are several differences in the way firefighters approach the scene of an incident involving an EV when compared to a standard ICE (Internal Combustion Engine) car. If the vehicle is on fire, once it’s extinguished they still have to consider the lithium-ion battery and the bank of cells inside – this has to be cooled as otherwise it could reignite. Recovery, too, is different – the likes of the AA deploy specially-trained personnel to recover damaged EVs. And if the damage is severe, there are even more factors to take into account.

“If the vehicle has been catastrophically damaged where there are exposed cables or if the electrolyte [inside the battery] has leaked, it’s explosive, it’s quite toxic. It’s all about recognising that – the electrolyte has got a glue-like smell,” Richard explains. “And how do you deal with electricity? You don’t take any chances whatsoever. There are electrical gloves, standard operational guidelines, and those copy and paste across to an EV when you’re dealing with exposed wires. It’s just thinking outside the box. You’re not looking at a fuse board now, you’re looking at a car on the road, but the principles are the same as regards your safety.”

The instances of catastrophic destruction are thankfully quite rare. In reality, as Richard agrees, EVs are often quite safer to deal with in the event of an incident. There’s no tank full of volatile fuel waiting to ignite, and there are less moving parts in the absence of an engine – power is provided via one or more motors. While EVs are in use by the likes of Dublin Port Tunnel, Dublin Port Authority, Dublin Airport and Liffey Valley Shopping Centre, alongside private early adopters, for the moment the chances of running into an EV-related RTC are relatively rare given the small number of them on our highways and byways. Still, DFB is ensuring it’s prepared for the day that petrol and diesel cars have a competitor with much greater volumes on the road. Richard is keeping on top of the latest developments, aided by Renault Ireland who supply electric cars for the purposes of training and keep DFB up-to-date with where the technology is progressing – the French company has made its own investment in EVs with the Twizy, Zoe and the Kangoo Z.E. van.

“EVs are around a long time and I think they’re going to be around for a lot longer than the combustion engine,” Richard says. “European and in fact worldwide manufacturers have decided electric is the way forward. We have to be proactive rather than reactive in how we’re dealing with the technology. It was important that it was recognised within the brigade that this was a change, and they have embraced it and moved forward with it very quickly.”

In addition, he touched on the need for resilience and their ability to bounce back – some of the calls received by emergency service controllers can take their toll, and care and support from their loved ones at home is very important to cope with trauma.

In addition, he touched on the need for resilience and their ability to bounce back – some of the calls received by emergency service controllers can take their toll, and care and support from their loved ones at home is very important to cope with trauma.