Former FDNY firefighter Tiernach Cassidy talks to Adam Hyland about surviving 9/11, honouring his colleagues and sharing his experiences

Most of us can recall where we were when the World Trade Center was attacked on September 11, 2001, but for FDNY firefighter Tiernach Cassidy, the memories of that fateful day will stay with him forever.

Stationed in downtown Manhattan, he witnessed the tragic events of the day unfold, and was one of only a handful of survivors from a squad that rushed to help as the Towers crashed to the ground.

Tiernach was part of Engine 3 in Chelsea, Lower Manhattan, but due to an injury he had sustained on a previous call out, he was assigned to light duties closer to the World Trade Center on Lafayette Street, between Spring and Prince Street. That morning, he had just arrived to begin what he thought would be another normal day, when events ensured it would be anything but.

“I got to work at 8.30am that morning and started to head up to the roof to have my first cup of coffee,” he tells me. “From the top of the building you could clearly see the World Trade Center, and it was a nice view to relax to before starting work. But that morning, the roof was packed with people. The first plane had just hit the North Tower. Everyone was asking: ‘What do we do?’ but we were told to stay where we were and await further instruction. We just didn’t know what had actually happened.

“Between us, looking back and forth from the rooftop to the TV in the fire house, we saw the second plane come in and hit the South Tower. At this point we all realised that this wasn’t an accident, we knew that this was an attack.”

With all available resources at 1st Division already sent to respond to the explosion in the North Tower, Tiernach and his colleagues knew they needed to help and rushed down the stairs. When another six-man team boarded their fire truck, Tiernach and a few others jumped on too, and headed to the site.

“On our way, the first tower was coming down, and we actually drove through the first collapse cloud to get there,” Tiernach tells me. “I used to live in that part of Manhattan, so the whole way down there I was telling the guys that I knew where to go, that I knew the area like the back of my hand, but suddenly it was unrecognisable, so we parked the rigs on Liberty and Broadway, and we started to work in groups to try to find survivors, because we could hear mayday signals.”

Tiernach and his colleagues rescued the few injured firefighters they could find and took them back to Broadway, before making their way back to the site of devastation.

“It was then that the second tower started to collapse,” he recalls. “We were right under it at this point. I remember the pancaking sound, but it took a few seconds to realise what that was. It seemed like time froze, but when I looked at the guy I was with, a lieutenant called Danny, we both realised it was the tower coming down. We ran back to our rig, he slid under it, and I opened all these compartment doors to build a little box for myself, to protect myself from whatever came down, and waited for the impact.

“After what seemed like forever, there was total silence, until all of a sudden, I started hearing the chirping of alarms. These were the sounds that our helmets emitted if we stopped moving for 30 seconds. The noise was coming from all around me.

“When the dust settled, I realised that, miraculously, me and the guys with me were still alive, and I was able to make out objects in the distance. We got up and went back to work, trying to find our friends who we knew were in there.”

While the emergency services did their best to clear the city, and as civilians fled, for Tiernach the next few hours were spent helping crews put out fires and searching for his colleagues and other survivors.

“Myself and Danny found ourselves in the very centre of the collapse,” Tiernach tells me, “and we were both tied off with lifesaving ropes, taking turns going into holes and looking for people. As I was holding the rope taut, Danny signalled that he had found people, and it turned out that there were 13 survivors. He signalled for help and when the rescue squad came in with stretchers, it was remarkable that nobody needed them, because everybody was able to walk out. It was unbelievable to come out of that pile.

“When I reached my hand down to pull the second guy out of the hole, I recognised him. He was Mickey Cross, a friend of mine from before we both went into the fire department. All he came out with was a scratch on his nose, and the first thing he did was ask me for was a cigarette. I was like: ‘Are you kidding me?’”

That initial success was sadly not to be repeated, much to Tiernach’s disappointment. “When we took those survivors out, I thought there would be hundreds more of them in the cavernous spaces of what was left of the World Trade Center. But there were none.

“In the immediate aftermath, just like in any accident, my first reaction is always to go and help. I saw it happen right in front of me, and I knew that hundreds of guys I worked with, and thousands of civilians working in the buildings, needed help, and in the back of my head, I assumed that almost everybody survived. I knew there would be a few fatalities, and a few injuries, but in my mind, I was thinking that there were so many people in there who needed help. ‘We are strong people, we will be ok,’ I was telling myself, because the reality was just incomprehensible.

“Of course, in the aftermath I was devastated to discover the amount of fatalities, but in the beginning, I was still thinking that if I just pulled back a rock, there would be 100 people sitting there saying ‘Oh thank God’. It didn’t work out like that.”

In total, 2,996 people lost their lives that day, including 72 police and 343 firefighters.

“Every fire house lost men,” Tiernach tells me. “From my own Fire House, Engine 3, we lost three guys from the truck, the chief and his aide, five good friends and colleagues. The fire house I was on duty with that day, lost almost everybody. The time that it happened meant there was a changeover of personnel. I would get into work at 8am, and the guys who would be finishing up on night duty would hang around and have breakfast, so we would have a double group in. When a major event like that happens, everybody wants to stay to help out, so not only did 20 Truck and Squad 18 lose their original six guys on the engine, but they had an additional six who had stayed and gone out with them. So, each squad lost 12 guys.”

Before 9/11

Despite the tragic events of that day, Tiernach is adamant that he “couldn’t imagine doing anything else” in what he still considers “the greatest job in the world”. Being a firefighter was one of the only things he had ever wanted to do. “As a kid, I decided that I either wanted to be a cowboy, an astronaut or a fireman. Those were my dreams,” he tells me.

“I didn’t have the schooling to become an astronaut, and I can’t ride a horse, so I became a fireman.”

He had been working in the restaurant and bar scene, “just like any good Irish-American lad would do”, and had waited patiently for six years for his call up after passing the written exam, before he was eventually sworn in on May 17, 1998. He was assigned to the same neighbourhood where he had tended bar, and one of the first fires he attended was in the bar he had been working in. “I’d been working there so long I don’t think anybody believed I was due to join the Fire Department,” he says, “but when I walked in and the manager saw me, he said ‘Holy shit, it’s Tiernach’. He invited us all in for a drink after our shift.”

Engine 3 in Chelsea covers the area from 28th Street to 14th Street, but also goes city-wide as a high-rise unit, covering any building over 80 foot, so Tiernach gained a lot of experience responding to a variety of calls in a busy neighbourhood, but his job changed dramatically after the World Trade Center attacks.

Ground Zero

On that first day, immediately after the attacks, Tiernach and his colleagues continued to search the area around the South Tower, without success, until reports came in to clear the area around Tower 7, which was on the verge of collapse. Following that, he continued to work through to 2am, when a relief squad was sent down.

“At first, I still had no thoughts of impending doom, because I thought we would find a large group of people alive,” Tiernach tells me. “After the first two weeks of digging and searching, people started talking about other scenarios, collapses at mines, and how long people could live without food and drink. But in the days that followed, reality started kicking in. Once we passed the point of no survival, we went on to recovery work, and that went on for a year or so after that.”

Crews altered between one month on operational duties and one month working at Ground Zero.

“I remember weeks after, the trucks would come in and dig out piles, and we were just looking for remains, just looking to give closure, to find some trace of a person. It is sad to think that we were just trying to find a piece or scrap, and thinking that was once a person you talked to. It really made you feel small.”

A permanent reminder

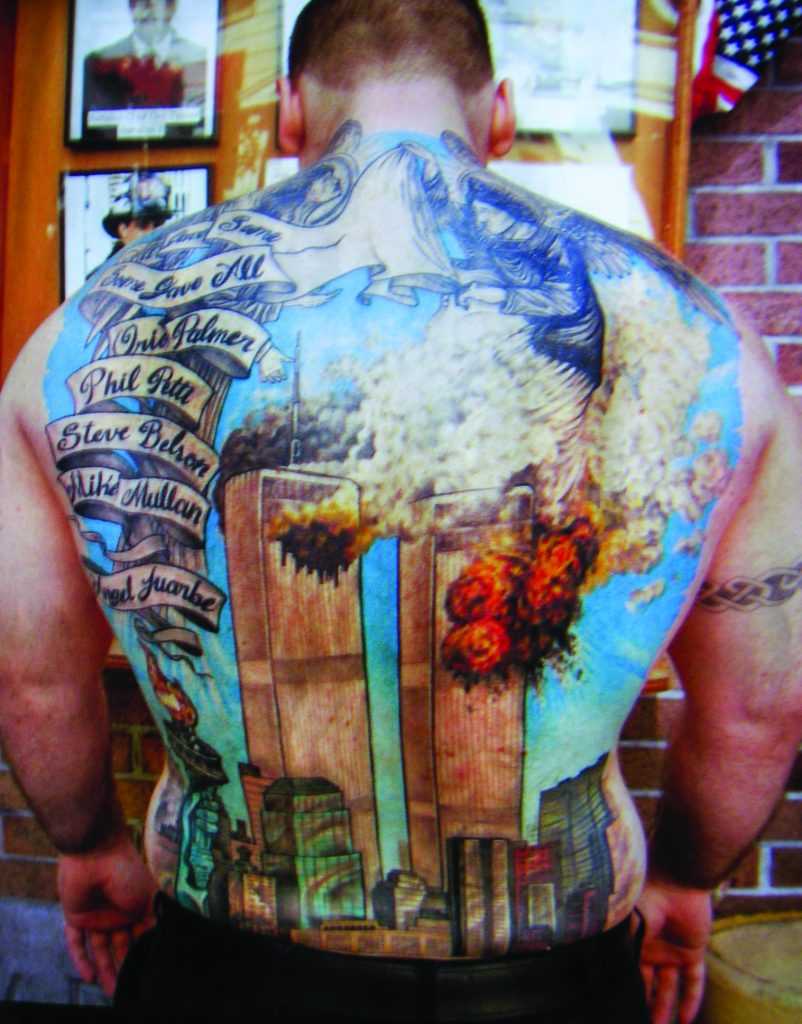

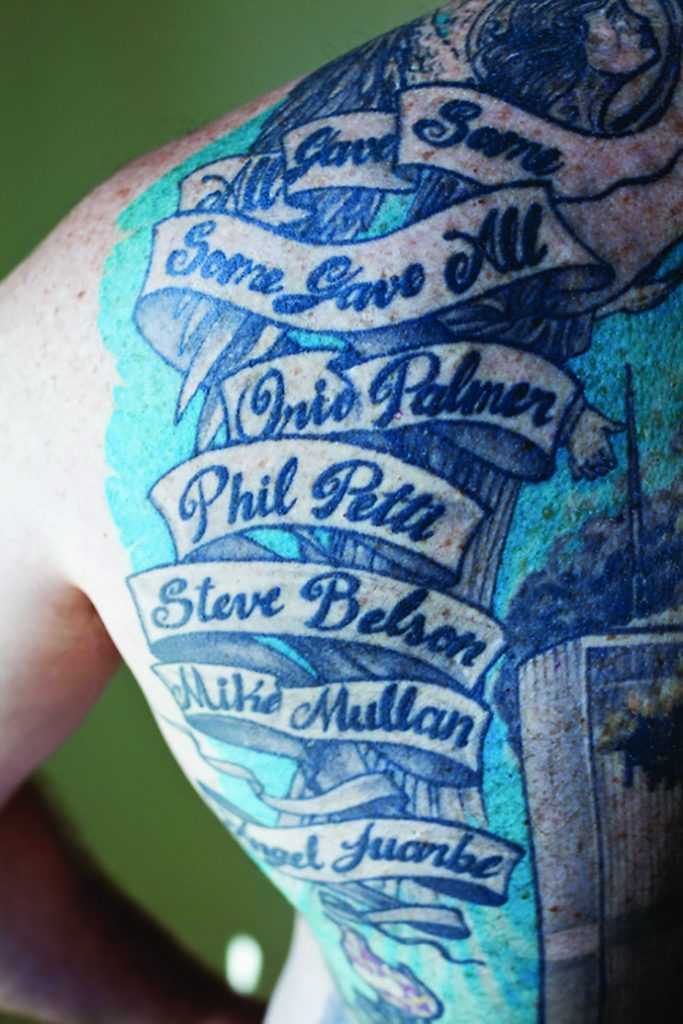

Tiernach says that his memories of that day will never fade, but he wanted to make a gesture to his fallen colleagues, and forge his own personal memorial to his friends at Engine 3. The result is a beautiful and poignant tattoo covering his entire back.

“After it went to a recovery effort, me and a lot of other active firefighters wanted some type of memorial to remember it by, so a bunch of us went to the local tattoo parlour, and walked in asking if we could get a group discount,” Tiernach tells me. “Firefighters are cheap!”

He continues: “For me, when I was on the roof of that building on Lafayette and saw that second plane come in and hit the South Tower, that image is still in my head, and I swear to God, I could feel the loss. To explain it is hard, but the emotion was so real. So that is what I put on my back – the towers, the smoke, an angel, and the names of the guys just from my firehouse, because unfortunately, I couldn’t fit everybody.

“It was therapeutic,” he says. “I went to, and still do go to counselling for this, and my counsellor said it was a form of pain therapy. Tattoos don’t feel good, if they did everybody would have one, but when I was getting this done, I don’t think I felt any pain at all. It took nine months from start to finish, going every two weeks, but I needed to do it, to remember and honour my friends.”

Tiernach is glad that he did it for another reason too. With regular sessions at the tattoo parlour, he became friendly with the receptionist, Christina. They are now married, with two children, Lucas, 15, and Isabelle, who is nine.

Once the recovery operation was wound down, the FDNY started to hire again in order to replenish its ranks, with a huge number of applicants looking to honour the city’s firefighters by taking up the mantle, and Tiernach found himself in an unexpected position.

“I still felt like the new guy,” he says. “I had only been in three years, there were guys with up to 25 years who I had listened to. But these new guys looked at anybody who had survived 9/11 as the senior guys. For a time, there was a lot of rebuilding and teaching the new guys the way I had been taught by the guys prior to me, which is how the fire department should be, and how it continues to be today.”

“It was a learning experience, especially for guys like me, to take the new guys under our wing, and still make the job a great job to be in.”

The Irish connection

As his name would suggest, Tiernach has a deep connection with Ireland, but in the past few years this has been strengthened by a surprising turn of events. Born in New York to Irish parents, as a child he moved to Dublin with his father for two and a half years before returning to the States, and until 1985, returned every summer to spend his holidays with his 18 uncles and aunts, and countless first cousins he likened to brothers and sisters.

It wasn’t until he was 17 when his mother revealed that he had an older brother in Ireland. “This is another crazy story all of its own,” Tiernach tells me. “My mother broke down one day and told me she had a baby when she was 19 or so. There always seemed to be a weight on her shoulders, but she never gave so much as hint about anything until that day.”

Having a child out of wedlock in 1950s Ireland meant Tiernach’s mother had to give her baby up for adoption while she worked in a convent before being shipped off to America. It was there that she met her husband, and soon Tiernach arrived on the scene.

“I had no idea about my brother Gerry, who is 12 years older than me,” he says, “and I never thought he would track us down. It was funny: When I found out at 17, I wondered how many times had I passed him in the street when I was visiting Ireland? Did I ever meet him? Stuff like that.”

Years later in Ireland, Gerry traced his mother through adoption and church records, and relatives, before finally getting in touch with her via a third-party.

“They started out writing letters,” Tiernach tells me, “before we arranged to meet. I remember picking my mother up to meet him at the airport. There were hundreds of people coming through customs, and I immediately picked him out. We don’t have the same physical stature or anything, but just like that, we just knew who the other was. My mother says we are like two peas in a pod. Nobody out here can fathom the story.”

Tiernach and Gerry have been “trying to catch up as much as possible” ever since, he tells me, with Tiernach visiting Ireland as much as he can. He transferred out of Engine 3 three years ago, moving out to the east end of Queens, “closer to home and a bit quieter than it was in the city”, before he left the FDNY on medical grounds. “As of last year, I am officially done,” he tells me, leaving him time to spend with his family, visit Ireland, and share his stories.

“It is definitely therapeutic to talk about it, and definitely don’t want to keep it bottled up,” he says. “I have plenty to tell and can go on for hours about what happened on 9/11, and. I would love to share my experience. The next time I am in Ireland, I would love to share my story with any fire service. That would be an honour for me.”

If you would like to arrange for Tiernach to talk at a station about his time in the FDNY, contact the editor for details of his next visit.