We look back at the annual FESSEF parade in Dublin city last September.

The annual Frontline and Emergency and Security Services Éire Forum (FESSEF) parade took to Dublin city’s streets once more last September, with around 1,000 emergency services personnel marching from Parnell Square to the grounds of Trinity College. A fantastic display of uniformed personnel, marching bands and gleaming machinery, the procession attracted large crowds of admirers along the parade route, led once more by members of An Garda Síochána on motorbikes and bicycles and passing underneath the national flag held aloft by two DFB appliances.

The marchers included Irish Army veterans, members of the Irish Prison Service, Dublin Fire Brigade (including the Pipe Band), An Garda Síochána, the National Ambulance Service, the Civil Defence, the RNLI, Order of Malta and more. “Frontline workers are out there to serve the public and that’s what we do as an organisation – always have and always will – and that’s what all the other services do as well. Days like this are always very positive because it creates more interagency activity and cooperation and it fosters one-to-one relationships when required,” Garda Chief Superintendent Kevin Gralton said at the launch of the event.

The parade concluded at Trinity College Dublin where a static showcase had been underway since earlier that morning. Various demonstrations were on view for the public milling around, including CPR, bomb disarmament, highline rescues and first aid. “It went really well and it’s building up,” explains DFB Third Officer John Keogh. “It’s an opportunity for the emergency services to be seen by the public all in the one area – the police, fire, ambulance, all of the volunteers who you are relying on to come together and help out in times of emergency. It’s a good showcase for the voluntary organisations and the emergency services to come together. To see us in a more social aspect is a big advantage and the kids get quite a kick out of it.”

There are other benefits for DFB and its colleagues in emergency response, including the chance to meet people and develop relationships, which could prove advantageous in the event of an incident. “The more and more that you meet these people, when it comes to a real event you know that you might recognise a face or you might know them by name,” T/O Keogh explains. He also makes the point that, as a national organisation celebrating national emergency services, the possibility of moving the annual parade outside Dublin on occasion should be considered. “Let the people in Cork, Limerick, Kilkenny, Killarney etc. have the parade down through their town to show what the emergency services are doing,” he adds. “There can be too much focus on Dublin at times – it would be nice to see it expand out around the country.”

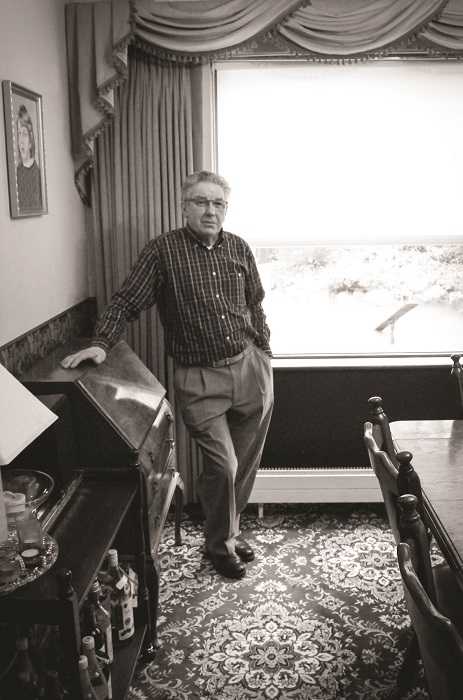

DFB’s colour party. Photos courtesy Trevor Hunt and John Keogh

ORGANISATION

The organisation of DFB’s involvement each year is no simple matter, with myriad tasks ranging from organising the flags to recruiting the colour party. Without volunteers, T/O Keogh notes, it simply wouldn’t happen. Twelve off-duty firefighters gave up their free time to march with each of the station flags, along with the Pipe Band and Dublin Fire Brigade flags; Ken Reynolds and Brian Campion volunteered to spend the day manning DFB’s presence in Trinity College, while Ger Corcoran and Declan Rice, C watch No 3, organised the colour party. The four appliances there on the day were all operational, ready to leave the parade in the event of an emergency. “We were quite prepared in the middle of the route if they had to drive off left or right and go to an incident,” says T/O Keogh. “It would show the 24/7 operation that DFB provides. The 999 ethos is that whether you’re having your dinner or you’re in a parade, if you have to go to an incident you just drop everything – the emergency event takes precedence.”

In 2017, FESSEF organisers added an extra day to the calendar of events, with a concert held at the Pro-Cathedral the evening before the parade. Featuring the musical talents of the Dublin Fire Brigade and National Ambulance Service Pipe Bands, as well as the Garda Band, tribute was paid to colleagues who lost their lives in the line of duty, including the crew of Coast Guard Rescue 116 and Garda Tony Golden. The Midlands Prison choir leant their voices to the evening, as did a section of RTÉ’s Philharmonic choir. Ticket sales from the event raised funds for Bumbleance, the RLNI charities, and O.N.E. (ex-service personnel). From DFB’s perspective, the Pipe Band put hours of practice into their performance, working with the National Ambulance Service Pipe Band to ensure both were playing at the same pitch, alongside several practice sessions with the Garda Band on timings. The DFB Pipe Band’s last collaboration with the NAS was playing with Andri Rae in the 3Arena; this was the first time the three principal response agencies in Dublin played as one.

“The concert on the Friday night was a huge success,” T/O Keogh explains. “By all accounts, from the people who were at it and paid their money, the show was a spectacle for them and spectacular in so many ways. Hopefully that will continue to build up over the years and get better and better.”