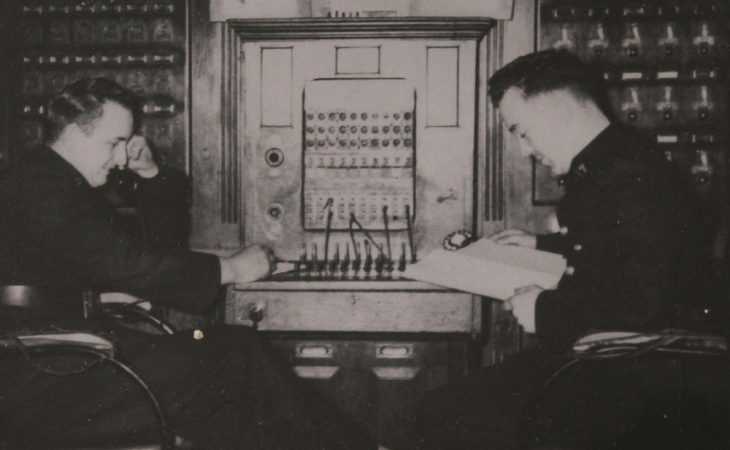

Michael Dineen (left) and F/F Michael Healy (right) on the switch at Tara Street in the 1950s

Conor Forrest sat down with retired D/O Michael Dineen to discover more about life in the fire brigade more than 50 years ago.

In their comprehensive book on the history of Dublin Fire Brigade, Tom Geraghty and Trevor Whitehead write of one of the worst attacks on the city of Dublin – something they refer to as the forgotten tragedy of the Troubles. The Dublin and Monaghan bombings took place on May 17th 1974, a series of co-ordinated explosions in both Dublin City and the centre of Monaghan town during rush hour. The first bomb was concealed inside a green Hillman Avenger on Parnell Street, and exploded at 5.30pm; the second went off at the same time on Talbot Street. The third exploded at 5.32pm on South Leinster Street, close to the railings of Trinity College. A fourth bomb went off around 6.58pm in Monaghan town centre. The streets of Dublin were busier as a result of a bus strike, but no warnings were given.

“The explosions were heard in both Tara Street and Buckingham Street fire stations so the men on duty hurried to the engine rooms. Soon the control room in headquarters was alive with calls and fire engines and ambulances were being dispatched to the scenes of the carnage,” the authors recount. The bombs killed 33 civilians (some count 34, as a full-term unborn child also lost its life), while around 300 people were injured. No-one has ever been charged for the deadliest attack of the Troubles.

“When the immediate shockwave of the ferocious blasts began to subside, the rescue crews arriving in the smokey darkness heard the first sounds and movements of the stunned victims. The scenes of carnage unfolded; there were wrecked cars, windowless buildings, debris-strewn streets, massive amounts of dust and floating paper. In the midst of all this mayhem were the cries of the maimed, the injured, the shocked and the traumatised. Due to a change of shift at 6pm crews were coming on duty to empty stations and those in Tara Street were dispatched in any vehicles available to assist at the dreadful sites. The emergency plan was immediately activated. All ambulances were routed to the terror-filled streets to be loaded with victims and rushed to the designated hospitals.”

Station photo, Tara Street, 1958. Michael is in the second row from the top, second on the left

Rescue operations were made difficult as a result of heavy traffic, and emergency vehicles had trouble getting through to the scene. Vehicles from DFB were aided by civilian cars, taxis, health board ambulances and a bus in a bid to remove the wounded and the dead from the scene, amid fears that further bombs would explode. “The working firemen had no time to wonder who was responsible as they searched the damaged buildings nearby for further casualties. Within four hours all those dead or requiring medical assistance had been removed to hospitals and the taped-off streets were deserted. Staff going off duty in the Dublin Fire Brigade were finally heading for home and trying to forget as much as possible the terrible trauma they had faced only hours before.”

One of these men was retired D/O Michael Dineen, he tells me, though understandably he doesn’t say much about what he witnessed on Dublin’s streets that day. “It was a sad day for the people that were killed,” he says. Attending such a grisly scene was difficult for all those who aided the sick and dying that day, as Michael notes. But, in the end, DFB’s firefighters had a job to do, and the mood didn’t change following the incident. “The fire brigade is the fire brigade,” Michael states sagely.

Michael was one of a number of firefighters present at another historic incident which took place in the capital in 1966. “I was there for the bombing in Sackville Place, when the pillar was bombed in 1966,” he explains. Built in 1808-1809, Nelson’s Pillar commemorated the famed British Navy officer, Horatio Nelson, and his victory at Trafalgar in November 1805. Despite criticism, it remained in place until March 8th 1966, when a bomb destroyed the upper structure of the pillar. The device had been planted by a number of former IRA volunteers, which some believe to have been in recognition of the 50th anniversary of the Easter Rising. Nobody was hurt, though a nearby taxi driver saw his car destroyed. Because it was too badly damaged, the Irish Army carried out a controlled demolition on the remainder of the pillar which, ironically, caused more damage on O’Connell Street than the original blast.

On duty at North Strand (front row, second from the right)

Humble beginnings

Michael is originally from a small farm in Ballyheigue, Co Kerry, and travelled to Dublin 1951 to take up employment as a barman in Phil O’Reilly’s on Hawkins Street. As some DFB members frequented the pub at the time, Michael came to hear that the fire brigade was recruiting. It helped, of course, that a healthy and active lifestyle was something he was interested in. “The lads of the fire brigade used to drink in the pub, and they said to me they were taking recruits over there [and asked me] ‘would you be interested?’”

Michael was very interested, and so began a long and enjoyable career with DFB. Beginning in 1955, he first spent a month in training at the Tara Street fire station, learning techniques and conducting pump and hose drills. Having completed his training, his first posting outside of HQ was to Dorset Street, followed by spells in Buckingham Street and Rathmines fire stations – all since closed. He can’t, however, choose a favourite station. “They were all pretty good. There was good comradeship in all the stations,” he says with a smile.

Throughout the proceeding years, and as he moved around the various stations, Michael’s career continued to develop. “I got promoted after seven years’ service, so I was a Sub/Officer.” The next step took him to the post of Station Officer, spending five years in Dolphin’s Barn and before he retired, he had achieved the rank of D/O, serving the final 12 years of his career in North Strand.

Michael’s retirement party, 1987

Different times

Life in DFB back in the 1950s was undoubtedly very different. The fire brigade’s remit during this period was expanding – the Factories Act of 1955 meant that DFB was taking on extra work, required to inspect more than 250 city factory plans, deal with certificates, inspect public places including resort and lottery premises, and other areas of concern. Two years later, in 1957, the auxiliary fire service was re-established, and chief fire officers across the country, including in Dublin, were tasked with training this new force. A 54-hour week would be reduced to a 45-hour week in June 1974, and down to 42 hours in April 1975.

At the time when Michael started, however, firefighters would work for a day and a night, and would then be on leave for a further day and night. Not one to complain, all Michael says of those times is “we didn’t mind, really,” and agreed that having spent such time in the station, it became a second family, a home from home, something which hasn’t changed to this day. One of the worst incidents Michael recalls was a fire at the Regent Hotel on D’Olier Street. “There were a couple of people burned,” he says. “The fire more or less went up through the hotel itself.”

Gas, however, was the major challenge, he tells me. Throughout his time in the brigade, a number of gas-related incidents claimed a number of lives, and levelled buildings. Tom Geraghty’s book, for example, notes a number of gas explosions, including one which destroyed two houses on Finn Street, in 1970, with two others suffering damage. Two months later, another explosion injured five people after a shoe shop on Glasnevin Hill went up in flames. “We were down in a block of flats down in the docks one day, and there were two lads who got gassed – the lads had to go in and pull them out. They (gas incident precautions) were pretty good [for example] you couldn’t switch anything on or off, or open the window,” he says.

But it wasn’t all pressure and stressful situations. Michael recalls several trips abroad, of a social nature, visiting firefighters in other countries to share their experiences. “The firemen were very good. We visited Belfast and talked to firemen up there, and we went to Cork, and I went to England and talked to the firemen there, and I [also] went to America.” One of the places he visited in the US was Secaucus, a small town in Hudson County, New Jersey, a 30-minute drive from New York City. Instead of finding differences, whether in perspective or the way in which they operated, Michael found that those firefighters operated to the same standards as those back home. “They were more or less on the same level,” he recounts.

Michael Dineen

These days

Now settled in Santry with his wife Philomena, to whom he has been married for 54 years, Michael is enjoying his retirement, effective since 1987, though he hasn’t simply sat back and watched the years go by. Once out of the job, he went to work with children with special needs in St. Michael’s House for 12 years, something he’s had an interest in for a long time now, and a calling echoed by his daughter and granddaughter. In his own words, it was an opportunity to give something back, to help those “who weren’t as lucky as we were.”

Though he has moved on and is making the most of civilian life, and as a regular with the Retired Members Association, he still keeps in touch with other retired members, sharing stories and trips across the country and beyond, it’s clear that Michael has fond memories. “I have no regrets and I enjoyed my time,” he tells me. “I worked in six different stations, with some of the very best firefighters.”